Art Share Documentation III

Thoughts in process: Art and Daily Life - Beyond Conceptual Art

The artist Amanda Heidel was present at the first meetings of the first Art Share group that I created at the Soil Factory in 2024. She then joined us in creating the Play Propagate group, where mothers and children meet to plant two garden plots and play together once a week. With her presence, I decided to propose creating an Art Share within the Play Propagate group, and we hold it on the first Thursday of every month.

This kind of commitment (setting aside one day per month to focus on a specific task) can be very helpful when creating art projects communally, especially when gathering groups of people who need to coordinate numerous activities in their lives. Heidel has been a lighthouse in upholding the basic value of Art Share, which is to keep the meetings happening by showcasing works in progress.

Observing Heidel’s work over the last year has been helpful to me in developing the initial thoughts I am introducing in this text, and I hope to further develop them in the coming year. They regard a conversation between making and theorizing that I’ve been pursuing since my PhD dissertation. In my dissertation, I sought to unveil the theoretical background that sustains the creation of artworks, arguing that every artist draws from a well of knowledge to maintain a consistent artistic practice. My question has been how an artist can figure out this knowledge for themselves, bringing it to the intellectual level, and creating, then, an autotheory (citing Lauren Fournier).

In my own autotheory, art-making makes explicit a person’s theoretical framework. In other words, an artist activates infinite connections between (often seemingly disparate) concepts and experiences while creating an artwork, and it is precisely the work of the artist to unveil these connections through the artwork. When I extrapolate this autotheory with the premise that every human creation can be understood as art, my autotheory becomes one that, within art history, expands the limits and practices of conceptual art.

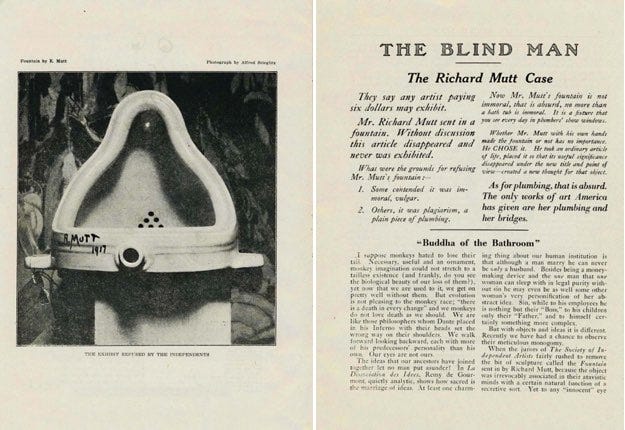

Within the discipline of art history and the art market, we typically trace the first artwork of conceptual art to Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), when he signed and dated a mass-produced porcelain urinal and presented it as an art object at an art fair. By prioritizing his thinking process over the creation of an object, Duchamp made evident the conceptual character of his artwork. One conceptual artwork, however, doesn’t make an entire theory, so although art historians can place the Fountain within the framework of conceptual art, Duchamp himself theorized about his work through the concept of the “readymade.” The readymade positioned the artist’s making on selecting a mass-produced object rather than on crafting, touching, or building an original object. The act of selection made explicit the artist's power to activate or create new connections between concepts.

Duchamp’s readymade theory is said to have transformed Western art history, but its conceptual emphasis created a radical gap that we continue to fill nowadays. Not for nothing did Duchamp need to create even the artist who signed the artwork. The radicality of the readymade is sustained by the distance imposed between the artist and the making, in order to sustain an intellectual capacity, making explicit an order of things, that is, an order of the art market that continues to exist nowadays: those who think don’t make, and those who make don’t think. However, as it is to be expected, over this more than one century since the Fountain, even though the art market continues to sustain these separations (we need them to determine the salaries and institutional positions), artists have continued to work beyond the market expectations, and particularly in conceptual art, a lot has been done to bridge meaning and making.

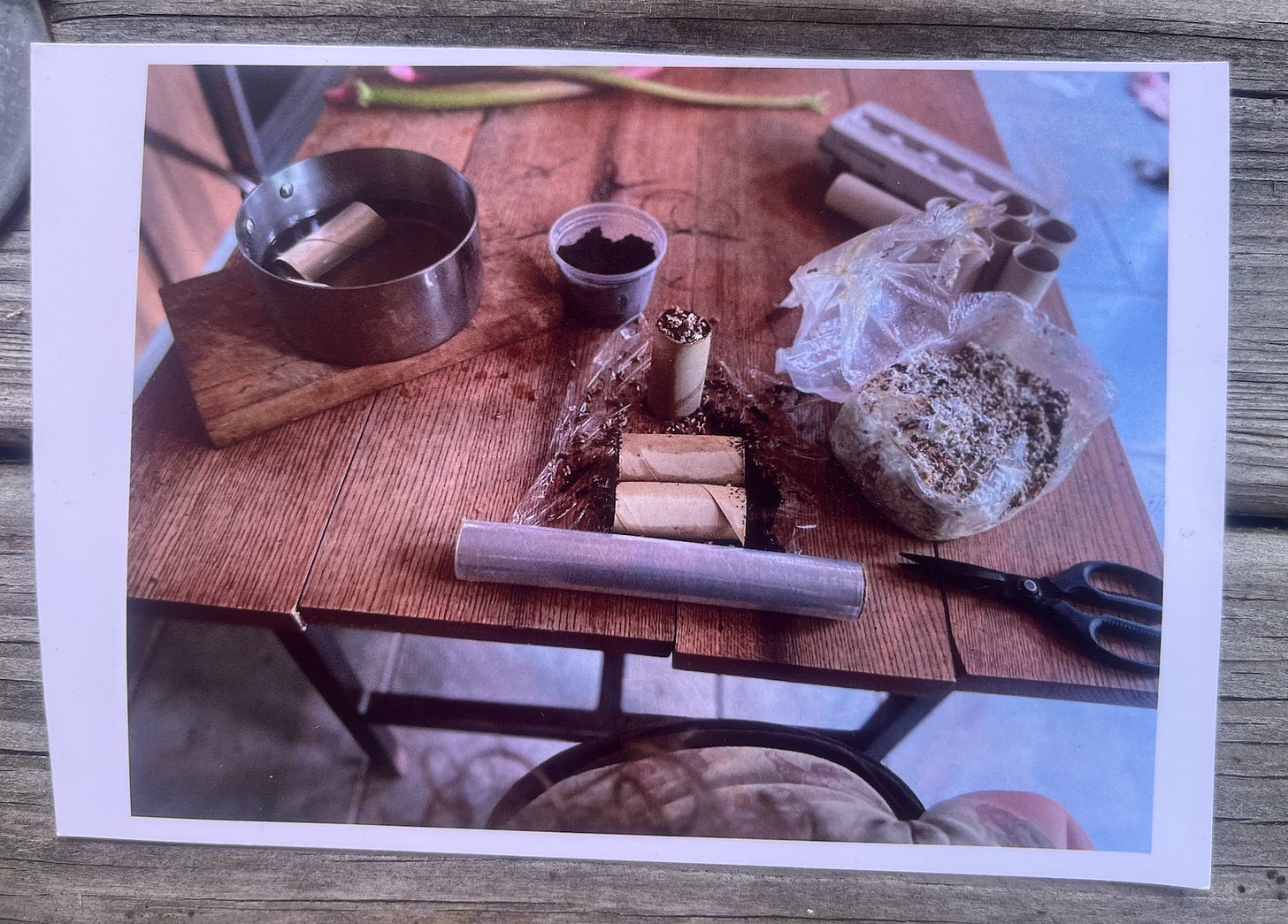

Heidel’s work relates to conceptual art because her art-making starts with isolating the concept of the mycelia, but then the way she has been making work, particularly after becoming a mother, greatly challenges any possible separation between concept and form, between thinking and handling. In our Art Share meeting, Frances Gallardo joked that Heidel got herself some assistants by using mushrooms in her work. Part of her making process involves creating the contents in which mushrooms can grow, which then become small sculptures with interesting shapes and textures. However, it isn’t the final object that makes the work, but the process of growing the mushrooms, and more explicitly, through her documentation efforts, the active intention of incorporating the making of these objects in daily life with her toddler Phoebe. Through participating in the Art Share group, Heidel is also highlighting the step in which the work doesn’t require her handling, when she needs to wait for the mushrooms to grow on their own.

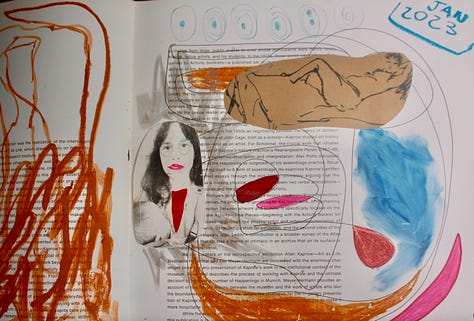

The question of daily life isn’t missed in Duchamp’s Fountain, after all, his choice of object was an urinal, pointing to one of the most basic, necessary, and daily life activities. In fact, throughout the 20th Century, many conceptual artists dealt with daily life and the question of how to extract, or how to notice, “art” in life. There is, however, something else, something that I’m still trying to figure out and that will remain underdeveloped in this text, regarding what is missing in conceptual art and its perception of daily life. I need to bring in more artists to this study/conversation. But I find hints of it in my attempts at daily artistic practice on the book “Art as Life” about Allan Kaprow.

My thinking process searches for a total integration of art and life by following the desire to understand for myself how a person can be an artist in all moments of their life. That is, I seek to reject the premise that certain activities are labelled as “art” while others are mandatory, professional, or otherwise. The same applies to thinking of certain objects created by humans as “art,” while others are less important and disregarded as utilitarian, up to becoming trash. This question, I believe, goes to the core of the capitalist material excess that drives our current culture, promoted on spiritual poverty, and leading us to environmental collapse.

Heidel’s work somehow sustains all these questions, too: an artwork that decomposes doesn’t become trash, it grows in nature and continues to live in other forms. A making process that takes place in the home with children holds the conceptual certainty of the existence and continuity of art that can’t be captured.

I still want to write about:

Madness. (Carl Jung, "Madness is a special form of the spirit and clings to all teachings and philosophies, but even more to daily life, since life itself is full of craziness and at bottom utterly illogical.")

Collectivity in art-making - Making with.

The making/not-making.

Motherhood – My body made the child, but I didn’t “make” them.