Pyrocolengos

A Pedagogical Perspective

On October 24, 2025, I taught two classes at Cornell University at the invitation of Prof. Denise Osborne. I intended to introduce students to three Brazilian artists and create an artwork with them. The artwork I created was Pyrocolengo, a collaborative work I’ve been developing over the past two years.

I first worked on Pyrocolengos during my artist residency at the Soil Factory in February 2024. At that point, the work was entirely conceptual, beginning with the formation of the word that gave it its title. Pyro from the Greek “fire,” Co from the Latin “together,” and Lengos playing with the Portuguese for línguas and léguas, meaning “language” and “distance.” The core idea of the Pyrocolengos is to have a painting inhabited by many people who will dance together.

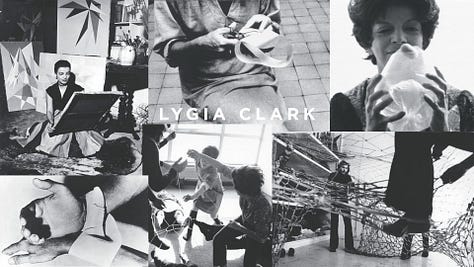

Pyrocolengos is directly related to Helio Oiticica’s Parangolés, which he began creating in 1964. Parangolés carried Oiticica’s ideal of the possibility of experiencing an artwork in its entirety, as he put it, “in-corporating the work in the body.” Unlike the Parangolés, Pyrocolengos are to be experienced with others, and don’t focus on the incorporation of an artwork, but on its making and fruition with others. In this sense, Pyrocolengos also relates to Lygia Pape’s Divisor (1968), in which many people share space under/inside a large cloth, and to Lygia Clark’s many “propositions,” in which the artist proposes activities for groups of people, and the making of these activities constitutes the work of art.

I approached my presentation at Cornell as an artwork in its totality, focusing on the making of a Pyrocolengo. However, the structure of a classroom and being invited to teach a class required me to think about the making of the artwork within the teaching framework. If I am in a similar situation in the future, I would be more explicit at the beginning of class about the steps for creating the artwork, and I would also introduce more experiences to help students feel immersed in an “art-making” situation, rather than just a lecture. Even though this wasn’t my first experience in this kind of context, the complexity of the artwork I intended to create made it challenging to navigate the connection between being an art historian and an artist simultaneously.

In the lecture structure, I favored the art historical component, introducing the Brazilian artists and the historical context in which they created their artworks, making it possible for students to work on their images while I taught, and then, at the end of the class, putting together the images they created on the piece of golden velvet I brought to compose the Pyrocolengo.

I taught the same lecture twice; however, in the first one, I wasn’t able to complete the entire process of making the Pyrocolengo, and in the second, even though I did complete the whole process, I wasn’t able to bring about the revolutionary capacity of Pyrocolengo. Instead, the challenging aspect of inhabiting an artwork together with someone else was more evident. In other words, my perception was that students, although willing to participate, weren’t fully integrated in the making of the work. Perhaps an extended period of making, in which we also made a circle for sewing their artworks together into the velvet piece I had to make a shared wearable, would be more successful.

Edit: After receiving the student evaluations from the class, I realized the art experience generated with Pyrocolengos was way more successful than I had imagined. Students were excited with what they created, had a deeper understanding of art-making with others and the potential for generating community, and expressed a clear understanding of the values I introduced related to Brazilian artists Oiticica, Clark, and Pape. The evaluations were also 100% positive regarding enthusiasm and a desire to create more art, which is one of my main goals.

Dancing Together

If in Coração I did a Pyrocolengo that focused on dancing, in this Pyrocolengo at Cornell, I only introduced the music and dance components of the work by the end of my presentation. I tried to teach students to play the samba rhythm with their bodies and encouraged everyone to do so, while others used the Pyrocolengo. A significantly longer time is needed to complete this part of the activity, or a more effective strategy is necessary to introduce people who are not interested in music and dance to the idea and desire to move their bodies. The classroom culturally requires us to make our bodies docile and disciplined, to sit and concentrate mentally on the lecture. It is tough to transition from a deep, conditioning mindset to a dancing, exposed disposition. This was, to me, a great reminder of the necessity of creating the right context and of clearly expressing to students the expectations and intentions behind the artworks. On the other hand, the difficulty of moving towards a dancing disposition clearly exemplified the potency of artworks like the Parangolés, effectively showing students, in their own bodies, the difficulty of actually “incorporating” the artwork. From a pedagogical and art-historical perspective, the “failure” of the artwork remains positive, demonstrating that integrating art-making and art-historical teaching is a successful strategy.

At the end of the class, I chatted with Prof. Osborne about teaching art and exposing students to different experiences. Prof. Osborne is a champion for students, and I discussed with her the necessity, as both an artist and a professor, to sustain the discomfort created by the diverse experiences we bring to our students. Experiencing diverse social interactions, like through the making of a collective artwork, or through watching a long artwork video like the one Prof. Osborne exemplified to me in our conversation, are pedagogical strategies to disrupt the usual perceptions of reality and create the oddness necessary to bring about new ways of thinking and acting in the world. For my own sake and for the sake of those with whom we live, finding ways to incorporate more dance and music into our learning experiences is fundamental to bridging the distance between thinking and relating to one another in the world.

I’m profoundly grateful to Prof. Osborne for this opportunity to think and make the Pyrocolengo in the classroom context, and to dance with me in the Pyrocolengo we created. These are experiences that will continue to reverberate in my practice and that I will continue to make meaning with in the years to come.